|

||

|

|

|

|

| West meets East |

|

Canadian composer Colin McPhee was not the first Westerner to have his life changed by Asian music. The French composer Claude Debussy, too, had heard a Javanese gamelan at the 1889 Paris World Exhibition, and tried to imitate its harmonies. But McPhee went further - much further - to Bali itself. He had spent the 1920s in New York City, writing highly rhythmic music of repeating patterns under the spell of Igor Stravinsky. By the late 1920s, according to his biographer Carol Oja, he was at a compositional impasse, disillusioned with writing esoteric music for small audiences. "Quite by accident," as McPhee put it, he heard some recordings of Balinese music released in 1928 on the Odeon label. [Balinese gamelan recording fades in beneath the following] "The clear, metallic sounds," he later wrote, "were like the stirring of a thousand bells, delicate, confused, with a sensuous charm, a mystery that was quite overpowering.... I returned the records, but I could not forget them. I knew little about the music of the East. I still believed that an artist must keep his mind on his own immediate world. But... after I had read... the quite fabulous accounts of these ancient and ceremonial orchestras, my imagination took fire, and... I determined to make a trip to the East to see them for myself." McPhee and his wife, the anthropologist Jane Belo, visited Bali for six months in 1931, and returned the follow year for a longer visit. They found a spot high in the hills near the little village of Sayan, perched on a mountain ridge, and built a house in Balinese style, made of bamboo and a thatched roof. There were no stores around, just an open market every other day, nor was there plumbing or electricity. McPhee interviewed Balinese musicians and eventually borrowed gamelan instruments and started his own gamelan - an orchestra of metallophones and gongs. The experience changed him forever. Returning to Paris when his visa expired, he "found himself 'restless' at concerts and claimed that 'the programs of new music that I once delighted in now seemed suddenly dull and intellectual.' He longed for the magic of the 'sunny music" of Bali." In 1936 McPhee wrote what would become and remain his most famous composition, Tabuh-Tabuhan. Half composition, half transcription, this was the first attempt to reproduce the patterns of Balinese music using a conventional European orchestra. From the very opening, it uses a simple four-note row in different permutations and at different rhythmic levels at once, just like much Balinese music. The second movement begins with a flute melody that is McPhee's own, but written in an exotic scale and sounding like a Balinese suling flute. The third movement is closest of all to Balinese music, basically an orchestral transcription of one of the Odeon recordings McPhee had found. However, even in this he was following Balinese practice, because composers of traditional Balinese music start with traditional melodic formulas and place them in new combinations. As McPhee himself wrote, "In Bali music is not composed but rearranged." In the year Tabuh-Tabuhan was written, 1936, Bali was becoming a popular place. One of the most popular songs on radio was called "On the Beach at Bali-Bali." McPhee and his wife returned to Bali in 1937, and complained about the ever-more-numerous tourists. "Many people from god-knows-where are building houses...," McPhee wrote. "Everyone wants to be Robinson Crusoe, and takes other footprints in the sand as personal insults." McPhee and his wife lived separately, however, because one of Balinese society's attractions for McPhee was its laissez-faire attitude toward homosexuality. That, however, didn't last. As the world geared up for World War II, the Dutch government cracked down on homosexual behavior in its territories, Bali included. McPhee escaped Bali in December, 1938, just days before a good friend, the ethnomusicologist Walter Spies, was imprisoned on a morals charge. Deprived of his island inspiration, McPhee lived out the rest of his lonely life in New York, writing very little music. We think of the United States as having been settled by Englishmen, Germans, Italians, French, Irish. Yet geographically, the United States is centered between Europe and Asia, and artistically, has benefitted from cultural waves in both directions. Many West Coast artists, in particular, grow up more attuned to Asia than to Europe. For instance, Henry Cowell, in many ways the father of American music, grew up in San Francisco between the Japanese and Chinese neighborhoods, where he sang his friends' songs in their native languages. Along with these influences Cowell studied classical violin, but he always claimed never to have really learned the European repertoire. All the same, however, the exoticism of Asian and African musics brings anxiety as well as inspiration. Unlike European and American art, which is generally secular and aesthetic in its intentions, the music of Eastern cultures is often tied to religious observance. Much of it expresses a philosophy that pervades the culture's total way of life, and therefore can't easily be taken out of context. Many American composers have been attracted by Asian music but doubted, as John Cage put it, "whether it was mine to study." Steve Reich, in a 1970 article called "Some Optimistic Predictions about the Future of Music," predicted that "Non-Western music in general and African, Indonesian, and Indian music in particular will serve as new structural models for Western musicians." But then he added, "Not as new models for sound. (That's the old exoticism trip.)" |

||||||||||

|

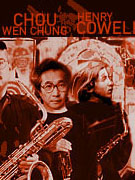

Years before someone coined the term "multiculturalism," Henry Cowell was one of the first to warn American composers against acquiring a superficial knowledge of non-Western music and pretending to have mastered it. In a 1963 article he wrote, "Most people who live in the middle and eastern parts of the country," he wrote, "don't realize that Japanese and Chinese music [are] part of American music." In Europe and America, Cowell noted, we have two scales: major and minor. In India, there are 72 fundamental scales that every child must learn before going on to the more advanced ones. Later, especially in the 1980s as multicultural awareness increased, there grew a strong liberal bias against what was called "appropriating" the art of another culture. This bias originated as a response to unfair situations in which white musicians had stolen techniques from musicians of color and gotten credit or wealth for them; for instance, Benny Goodman profiting from Fletcher Henderson's band arrangements in the 1930s, or Elvis Presley getting famous singing in a style stolen from black vocalists. From such perceptions of historical unfairness came a distaste for any white musician imitating musical methods from a culture outside his or her own. Even McPhee himself had recorded doubts about his right to appropriate Balinese music. "Just how much, and in what manner a so-called primitive music can be utilized by the occidental composer," he wrote, "is a question for each individual conscience. The difference between a pastiche and a creative work in which foreign material has been so absorbed by the artist as to become part of his equipment is something which has never been completely recognized." Nevertheless, many composers have insisted that American music not only can, but must, learn from musical cultures around the world. As Henry Cowell wrote in 1948, "It seems to me certain that future progress in creative music for composers of the Western world must inevitably go towards the exploration and integration of elements drawn from more than one of the world's cultures." And today, as African and Asian musics are more and more taught in universities as part of a standard curriculum, more and more young composers reach maturity trained in a multiplicity of traditions. Cowell, for example, not only grew up near Japanese and Chinese neighborhoods; he studied with one of the early pioneering ethnomusicologists, Charles Seeger. Cowell's acquaintance with world musics increased vastly during World War II. As an employee of the Office of War Information, he was in charge of learning how the government and military could best use music for cultural purposes. He had to find Persian music for radio transmissions to Persia; Italian music to broadcast after the Allies invaded Italy; Japanese love songs that could make Japanese soldiers homesick - sometimes under conditions in which all recordings had been destroyed by the enemy army. Since Japanese propaganda claimed that the Americans would try to convert any defeated countries to Christianity, Cowell had to avoid beaming any music to Japan that had strong religious connotations one way or another. Lacking recordings of Thai music, he found members of the Royal Thai Legation in Washington to make records for him. Following the war, Cowell compiled and annotated a groundbreaking series of recordings of music from all over the world for Folkways records. In 1956 and '57 he and his wife spent 14 months in Asia, sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation, the USIA, and the US State Department. Acting as music consultant for Teheran Radio, he wrote a piece called Persian Set, combining European and persian instruments. In Japan he wrote an orchestral work, Ongaku, with motives and scales based on the Japanese court style of music known as gagaku. Back in America, Cowell wrote a suite called Homage to Iran for the Iranian violinist Leopold Avakian, accompanied by Persian drum and piano; Avakian played the work in 1959 for the Shah of Iran. Having lived long before "appropriation" became an issue, Cowell believed in a musical "open market" in which musicians from all over the world were free to learn from each other. Like Cowell, Harry Partch was born in California. He was the son of Presbyterian missionaries who had fled China during the Boxer rebellion, and who were soon transferred to Arizona after Partch was born. Partch grew up hearing Chinese lullabies, and also the songs of the Yaqui Indians and Mexicans who lived in the area. At the University of California, he found the European approach to music suffocating, and felt that his professors knew no more than he did. "In the early days of presenting my music," Partch would later write, "the mere mention of the words Bach or Beethoven, twin gods of classical musicians, turned on a faucet of revolt in me." Unencumbered by any sense of indebtedness to Europe, Partch invented his own eclectic brand of music theater from Japanese, Chinese, African, American Indian, and ancient Greek elements. He called his music "corporeal," meaning that it existed in three-dimensional theatrical space, not in the abstract sonic plane of European music. Thanks to his study of the acoustics of music in the works of Helmholtz, he rejected the 12-pitch tuning of Western music and invented a new scale with 43 pitches to the octave, one that would allow the kinds of tunings found in Asia and ancient Greece. He invented his own fantastical gallery of instruments to play this scale, including the Chromelodeon, Diamond Marimba, Kithara, and Quadrangularis Reversum. He insisted that his musicians form in costume, and that the form of his instruments be visually beautiful. Partch's opera Delusion of the Fury, which many consider his greatest work, has a first act based on Japanese Noh theater, and a second act based on African story telling. In the second act, a deaf hobo gets in an argument with an old woman over a goat. At the trial, the superbly near-sighted judge says to the hobo (as the old woman holds the goat), "Young man, take your beautiful young wife and your charming child and go home, and never let me see you in this court again!" The chorus responds with a joyous refrain: "Oh how would we ever get by without justice!" Oregon native Lou Harrison took Henry Cowell's "Music of the Peoples of the World" at the University of California in San Francisco in 1935. Nevertheless, he composed un a dissonant, often 12-tone style until the late 1940s. Living for awhile in New York, Harrison had a nervous breakdown in 1947, and spent nine months recuperating. He emerged with a simple, beautiful work called The Perilous Chapel, indebted to several Asian styles. In 1961 Harrison was a delegate to the East-West Music Encounter in Tokyo, and afterward spent several months in Korea and Taiwan studying, among other instruments, the double-reed Korean p'iri and a Chinese psaltery called the zheng. From this point on, Harrison would frequently call for Asian instruments in his works. Most significantly, Harrison became the first major Western composer for the gamelan itself. In 1967 he met and became partners with the electrician and amateur musician William Colvig; the two afterward collaborated on homemade gamelans and other instruments capable of playing Asian tunings. Many of Harrison's subsequent works featured a mixture of European and Indonesian instruments, including his Suite for Violin and American Gamelan. Harrison was also a student of Esperanto, the invented language that was developed in hopes that it would become a universal language. And when Harrison set the Buddhist scripture, the Heart Sutra, to music, using chorus, harp, organ, and gamelan, he did it in Esperanto, in an attempt to make a truly universal work. Other American composers had more indirect reactions to Asian music and thought. After World War II Cowell's student John Cage came to a crisis of conscience about his music. He considered going into psychotherapy, but, "in the nick of time" as he later put it, he met a student from India named Gita Sarabhai. Dismayed at the bad influence Western music was having on the traditional musics of India, Sarabhai had come to study European music for six months, so that she would understand what she was up against, before going back to help preserve Indian traditions. She studied counterpoint and contemporary music with Cage, who offered to teach her for free if she would also teach him about Indian music. Before leaving, she offered Cage a copy of The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, a book that Cage later said "took the place of psychoanalysis." In Indian musical theory Cage doscovered the nine Indian emotions: love, wonder, laughter, heroism, fear, sorrow, anger, disgust, and tranquility. He attempted to depict these emotions in his magnum opus of the 1940s, Sonatas and Interludes for prepared piano, an instrument in which the strings were modified by objects like bolts and washers. Other books on Eastern thought had an impact as well. A young protege named Christian Wolff brought Cage a copy of a book his father had published, a new translation of the Chinese Book of Changes, more commonly known as the I Ching. The I Ching is an oracle in which 64 situations are described, the appropriate one determined at random by throwing yarrow sticks or, more modernly, by tossing coins. Fascinated, Cage became a devotee of the I Ching, and began using it to determine compositional choices in his music. In 1951-52 he wrote an hour-long piano work entirely by tossing coins, called Music of Changes. The idea behind the piece was that every random choice of the I Ching was the universe's correct choice for that moment, and that therefore mistakes were impossible. In 1952, Cage went even further. Inspired by his readings in Asian philosophy, and also by the entirely white paintings of Robert Rauschenberg, he wrote one of the most notorious pieces in American history: 4'33". This consisted of four minutes and 33 seconds of silence, divided into three movements, and first performed on August 29, 1952, at - appropriately enough - the Maverick Concert Hall, an outdoor space in Woodstock, New York. Outraged listeners sometimes ask whether John Cage was really paid good money for writing four and a half minutes of silence. Of course he wasn't. Like many other composers, Cage frequently made no money from his music, and in those days still held the occasional menial job when teaching wasn't available. Many years later, however, when he was famous, he was able to sell the original manuscript of the piece. Cage was inspired by not only the I Ching but Zen Buddhism, and quoted in his book Zen koans, or nonsensical and unanswerable riddles used by Zen monks to provoke enlightenment. Cage urged listeners, though, not to blame Zen for his music. Certainly there is nothing in any Asian traditional music that sounds remotely like Cage's chance music, nor even like 4'33". But there is in Cage's late music a tranquility, an impersonality, a calm acceptance of sound for its own sake, that seems more related to Eastern philosophies than to anything American or European. In the hippie-dominated 1960s, influence of Eastern music and religions flourished. Even the Beatles went to India and added sitars to their recordings. All the well-known minimalist composers took inspiration from Eastern musics. In summer of 1970, Steve Reich visited Accra, the capital of Ghana, to study drumming with Gideon Alorworye, a master drummer of the Ewe tribe. According to Reich, he had a daily lesson that was taped, and afterward he would take the tape back to his room, and, by playing it at one-half or one-quarter speed, he would be able to transcribe the bell, rattle, and drum patterns into notation. Reich caught malaria and returned after only five weeks, but he supplemented his studies with a book by A. M. Jones that has been an important resource for many musicians: Studies in African Music. And upon Reich's return to New York, he wrote his first major work, the work that would put him on the map: Drumming. Drumming did not imitate African idioms; instead, it employed a phase-shifting technique Reich had already used in pieces like Come Out and Piano Phase. But it was in 12/8 meter like most music of the Ewe tribe, and was emboldened by what Reich calls the "confirmation" he received from his studies in Ghana. La Monte Young and Terry Riley, meanwhile, traveled to India and the Himalayas. In contrast to Reich's interest in rhythm, they were more interested in purity of harmony, and India had perhaps the most sophisticated pitch sense of any music in the world. In the Himalayas they met a teacher, Pandit Pran Nath and both Young and Riley have been seen singing Indian ragas, for practice at home and also in public as well, since around 1970. Especially with Riley, this style of singing has often infected his composed music. For La Monte Young, the Indian influence has shown up most in his vocal improvisations of the 1960s with the Theatre of Eternal Music, and also in Young's magnum opus, The Well-Tuned Piano. The Theatre of Eternal Music was an improvising group that included Tony Conrad, Marian Zazeela, and John Cale; Cale later became famous with the Velvet Underground. During the '60s, they would play very loud drones and improvise perfect consonances over them with voices, violin, and viola, in deafening performances that would go on for hours. Young's magnum opus is The Well-Tuned Piano, a six-hour, improvisatory piano work in a very unusual tuning, using intervals derived not from European harmony, but from Arabic and Indian tuning systems. Many of these intervals are one third of a half-step flat from the harmonies we're used to, but quite common in Arabic and Indian music. For six hours, Young improvises around a series of about fifty themes and cadences, with an attentiveness to sound similar to an Indian violinist or singer. Phillip Glass's turn to minimalism also had to do with Indian music. In 1965, Glass was in Paris, where he was asked to transcribe some music by the Indian sitar player Ravi Shankar that was intended for use in a film. Working for months with Shankar and his tabla player, Glass learned the principles of Indian rhythmic structure, or tala, in which rhythmic cycles are built up by addition of different numbers of a small rhythmic unit. Under this influence, Glass began working in a new style using repetitions of tiny rhythmic patterns and very few pitches, a style that first appeared in his 1965 music for Samuel Beckett's Play. Back in New York, while working with Steve Reich, Glass would turn the rhythmic cycles of Indian music into his early, rhythmically irregular style in such works as Music in Changing Parts. Glass would ultimately repay his debt to Indian music with Satyagraha, an opera about Mahatma Gandhi, sung in Sanskrit. Thanks to tremendous gains in the field of ethnomusicology, Asian and African musics are now a permanent part of the young musician's musical landscape. Indonesian-style performance is particularly common - there are more than 200 gamelan ensembles in the United States, with dozens of composers writing for them, like Barbara Benary, Jared Powell, and Jody Diamond. In addition to people of European descent learning to play in Asian and African traditions, however, there is an increasing counterflow of Asian-American and African-American composers working in idioms that reflect a mixture of cultures. The first Asian-American composer of note was Chou Wen-chung. Born in Chefoo, China, in 1923, Chou came to Yale to study architecture, but switched to New England Conservatory to study music. His works were influenced by his teacher Varèse and by the general turn toward pointillistic music, but were often based on Chinese subjects, with a sensitivity to timbre and pitch-bending. |

||||||||||

|

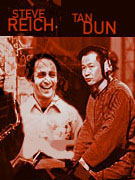

Since Chou there have been many Asian-American composers, many of them brought here through a pipeline involving Columbia University: Chen Yi, Jhou Long, Bun-Ching Lam, Bright Sheng, and most notably Tan Dun, best known for having written the award-winning film score for the film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. Born in Si Mao village in central Hunan, Tan Dun grew up in a traditional, rural Chinese village, planting rice during the Cultural Revolution. Working as a fiddle player and arranger for a provincial opera troupe he was selected for the Central Conservatory of Beijing, where he spent eight years. As the restrictions of the Cultural Revolution were lifted, Tan discovered a world of 20th-century music that had been previously suppressed, and was influenced by it. This made his music controversial in China, and it was officially declared "spiritual pollution" in 1983. In 1986 he managed to come to Columbia, where he studied with Chou Wen-chung and others. Tan Dun describes himself as a composer "swinging and swimming freely among different cultures," and his music is a deliberate mixture of styles. Within what he calls "the concentrated lyrical language of Western atonality" he mixes exotic timbres: glissandos, struck bowls filled with water, ceramic percussion instruments, often contrasting an active Western musical style with an Eastern sense of timelessness. If there is any constant which characterizes the Asian influence on American music, it is the perception that European music is about forward motion toward goals and climaxes, whereas Asian music has a sense of timelessness, changelessness, and tranquility. This aspect of some American music, the ability to hover in time without the music needing to go anywhere or change, can be heard as an Asian influence or aesthetic anywhere it occurs, from the chance music of John Cage to La Monte Young's minimalist piano doodling to a Lou Harrison sutra setting to a Tan Dun film score. In fact, timelessness and forward motion are two complementary aspects that could exist in any music: music has the potential to sustain and repeat elements without changing, but also to create metaphors for the irreversible passage of time. As inheritors of a European mindset, we usually identify with the forward motion aspect of music and project timelessness onto Asian aesthetics. Yet when John Cage found an ancient Indian definition of the purpose of music - "to quiet the mind and render it susceptible to divine influences" - his friend Lou Harrison found the same definition in writings by a composer in Renaissance England. Still, there are other ways to bring the spirit of Asia into American music. Asian-American composer and baritone saxophonist Fred Wei-han Ho infuses a basic jazz vocabulary with strong doses of Asian sonic iconography. Gongs and pitch-bending squeals dot his scores, and his favorite sax technique is an altissimo wail that he achieves without fingering, through sheer lip pressure. He writes his vocal works in non-Western languages - Cantonese, Mandarin, Tegalog, Farsi - and uses Tai-Chi-trained choreographers for his operas. Unlike most other prominent Asian-American composers, Ho was born here, and grew up in Amherst, Massachusetts, where he was lucky enough to come in contact there with jazz greats Archie Shepp, Max Roach, and Reggie Workman. He claims that certain Asian-American composers get championed by the classical music establishment "because they are considered "safe" - their work will not confront issues of racism, oppression, resistance, and struggle, as the expressions of oppressed nationalities (so called peoples of color) in the U.S. tend to do. Confronting racism and oppression is the essence of Ho's work. His operas, like Journey Beyond the West: The New Adventures of Monkey and Warrior Sisters, use a punchy, provocative big-band idiom to tell stories of brave bands of companions fighting against corrupt capitalism. Of course, the African influence on American music is even larger - too large to tackle in one program, though it has already been partly covered in "It Don't Mean a Thing If It Ain't Got that Swing," our program on jazz influence in American music. In upcoming programs of "American Mavericks" we'll also explore minimalism; the changing relevance of the orchestra; and the invasion of rock beats into classical music.

|

||||||||||

|

|||||

| American Mavericks | Archive | About | Contact | Stations | Features | Press | Listening Room | Discussion | Purchase | |||||